The Fracking Industry's Methane Problem Is a Climate Problem

Methane is shorter-lived in the atmosphere but 85 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20 year period.

While carbon dioxide — deservedly — gets a bad rap when it comes to climate change, about 40 percent of global warming actually can be attributed to the powerful greenhouse gas methane, according to the 2013 IPCC report. This makes addressing methane emissions critical to stopping additional warming, especially in the near future. Methane is shorter-lived in the atmosphere but 85 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20 year period.

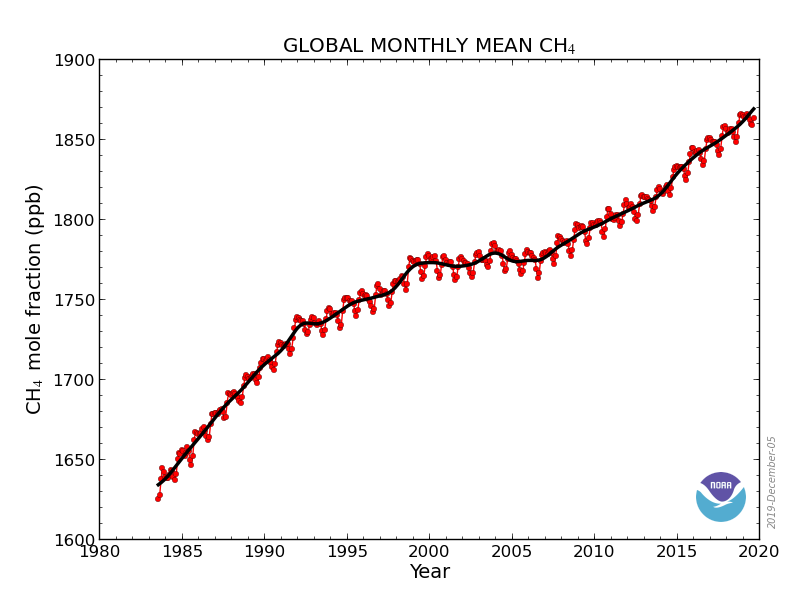

Atmospheric levels of methane stopped increasing around the year 2000 and at the time were expected to decrease in the future. However, they began increasing again in the last 10 years, spurring researchers to explore why. Robert Howarth, a biogeochemist at Cornell University, recently presented his latest research linking the increase in methane to fossil fuel production, with fracking for natural gas, which is mostly methane, likely a major source.

Global Monthly Mean CH4 (Methane) Credit: NOAA Earth System Resource Laboratory, Global Monitoring Division

In a December 14 research presentation in Ithaca, New York, Howarth argued that 3.4 percent of all natural gas produced from shale in the U.S. is leaked throughout the production cycle.

For the latest on shale gas, methane, and climate change, check out my lecture in Ithaca on Dec 14.https://t.co/mP3UjX6yNb

— Robert Howarth (@howarth_cornell) December 17, 2019

Howarth’s research links the increase in methane to the U.S. production of shale gas via fracking. The beginning of the U.S. fracking boom coincides with the beginning of the rise in methane in the past decade, and a 2018 NASAstudy linked the industry to this methane spike.

One thing that is becoming increasingly clear about the U.S. fracked oil and gas industry is that it leaks methane — a lot of methane. About 60 percent more methane than previous Environmental Protection Agency estimates, which relied heavily on industry self-reporting, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Science.

Leaks, Venting, and Blowouts

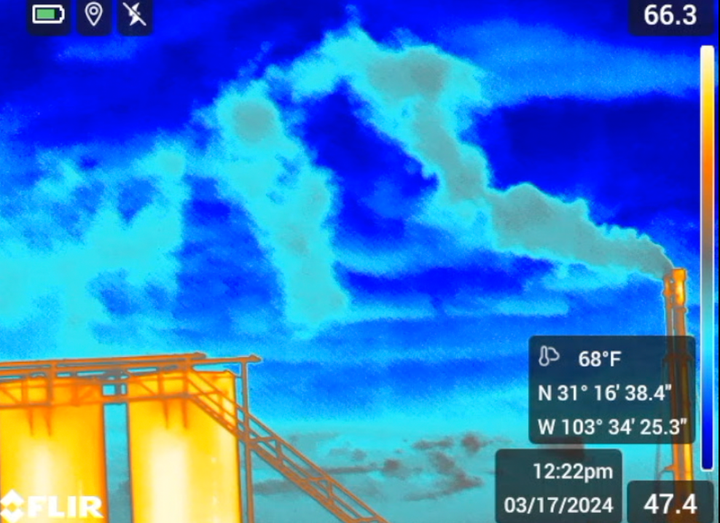

While the oil and gas industry makes claims about wanting to reduce methane leaks, it has been aided by two simple facts that help hide the scale of the problem: Methane is odorless and invisible to the naked eye. Difficult to detect, methane leaks in the oil and gas production system weren’t obvious until people like Sharon Wilson at Earthworks began bringing specialized infrared cameras to production facilities and helped make those leaks visible.

But it isn’t just unintentional leaks. Much of the methane released is intentionally “vented” to the atmosphere in areas without the processing plants, pipelines, and other expensive infrastructure to make use of it.

Recently, Wilson took The New York Times to Texas to document the severity of the situation. When the Times showed the results to Tim Doty, a former senior official at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality who is trained in infrared leak detection, he commented, “That’s a crazy amount of emissions.”

Meanwhile, the American Petroleum Institute, the largest U.S. oil and gas industry trade group, has been running misleading ads this fall, claiming the industry has reduced emissions even as it successfully lobbied the Trump administration to roll back new regulations designed to reduce methane emissions.

This month, Texans for Natural Gas, the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, and the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association released a report claiming relatively low flaring rates and that “methane emissions intensity” is down for the prolific Permian oil fields. However, according to E&E News, analysts at Rystad Energy reported in November that flaring, or burning, natural gas in the Permian has hit an “all-time high.”

Where are federal regulators? Letting industry self-audit. Susan Bodine, assistant director for EPA enforcement and compliance, said of the need for oil and gas well operators to monitor and control pollutants, “We know it is a widespread problem. We feel the best way to get them back into compliance is for them to do it themselves.”

Two reasons the industry is reluctant to invest in methane emissions reduction equipment and infrastructure in places like Texas — even though it is in the business of selling methane as natural gas — are the oversupply of natural gas produced in America and historically low natural gas prices. This is in large part due to what’s known as “associated gas.”

Associated gas is a byproduct of fracked oil wells. Oil well operators make most of their money selling oil, which fetches a higher price, and either burn off (flare) or release (“vent”) the associated gas into the atmosphere, as the infrared cameras make clear.

At certain points this year, the price for natural gas in Texas went negative. The industry has little economic incentive to stop leaks of a product that has no value.

In addition to the ongoing leaks that are part of daily operations, the oil and gas industry also has experienced accidents resulting in major methane leaks.

The Aliso Canyon methane leak in California in 2015 was the largest documented methane leak in U.S.history, leaking from a natural gas storage facility for 118 days. The scale of the leak was comparable to the annual emissions of half a million cars. According to Thomas Ryerson, a research chemist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the accident was a major step back for the climate. “On the scale of the control efforts that have been put in place to minimize greenhouse gas emissions, it rolls that back years,” he told Smithsonian Magazine.

Along with the infrared cameras that can “see” methane leaks, satellites are now offering another way to track leaks, and the early reports aren’t good. The New York Times reported this week that scientists determined a blown-out gas well in Ohio was a major methane leak — much larger than the well’s owner ExxonMobil had reported.

The oil and gas industry has been able to deny the scale of the methane problem for a long time because outside validation was scarce and few could prove companies weren’t accurately reporting the numbers. These new technologies now allow those outside of industry to quantify the true scale of the methane problem.

Knowing the scale of the problem is one thing, but having regulators who will hold the industry accountable for addressing it is a whole other problem.

Bridge Fuel Propaganda

Natural gas is still a fossil fuel — just like coal and oil — and despite well-funded industry efforts to promote natural gas as a climate solution, its methane problem makes it a major contributor to the climate crisis. The natural gas industry has hailed it as a “bridge fuel” that offers a “cleaner” energy option to bridge society’s transition to renewables. Much like the “clean coal” effort, this is nothing more than a marketing campaign to confuse the public and sell natural gas.

Yet the industry gets help in this effort from politicians from both political parties in the U.S. The Obama administration oversaw the massive expansion of fracking over its eight years and promoted the idea of natural gas as a bridge fuel. Former members of Obama’s administration continue to do just that, including former Vice President and current Democratic presidential hopeful Joe Biden, whose top energy advisor Heather Zichal, after leaving the administration, was appointed to the board of natural gas company Cheniere Energy.

High profile efforts to address climate change have allowed the bridge fuel myth to linger. Former Secretary of State John Kerry recently launched World War Zero, a celebrity-backed initiative to rally “unlikely allies” to respond to the climate emergency. Among those allies are proponents, such as former Ohio governor John Kasich, who are still advocating for natural gas as a bridge fuel. “If I’ve got to sign up to be an anti-fracker, count me out,” Kasich told The New York Times.

As the scale of natural gas’s methane problem becomes even clearer, the idea of natural gas as a “bridge fuel” loses its credibility. Especially when power generation from solar, wind, and battery storage, which are growing rapidly, are already cheaper than coal and competitive with natural gas in many places.

Industry Back to Challenging Science and Misleading the Public

For decades, the oil and gas industry has effectively delayed climate action by misleading the public and funding politicians to do the same by pretending there was a debate about the science. It worked.

The industry is applying the same approach to natural gas. It releases ads with misleading messages saying it has achieved a “60 Percent Reduction in Emissions” (when it’s a reduction in emissions rates in some areas), along with relentless messaging about how natural gas is “clean” and key to fighting global warming.

The oil and gas industry knows it has a methane problem, and a methane problem is inherently a climate problem. But the same industry that sought to sow doubt about climate science is sticking to its proven approach of misleading the public with pretty advertisements and compliant politicians.

However, efforts by activists like Sharon Wilson and scientists like Robert Howarth have revealed the invisible climate bomb that is methane. And that reality has the industry worried.

Scott Sheffield is CEO of Pioneer Resources and a veteran of the fracking industry. He is on the record saying he believes the industry has to stop flaring and venting so much methane. Sheffield sees risk ahead.

“Climate change and investors are the two big challenges,” he told the Wall Street Journal.

Sheffield understands the reality. As the scale of the fracking industry’s methane problem becomes more widely known, the true impact of fracking for oil and gas becomes crystal clear. Burning oil and gas is a significant contributor to climate change, but even before these fossil fuels make it into a car or power plant, we now know that so is simply producing them.

Main image: Methane sign. Credit: Jeremy Buckingham, CC BY 2.0

This article originally appeared on DeSmog.

Comments ()