New Methane Regulations Unlikely to Change Oil Industry Behavior

It is unlikely that the new methane regulations will have the large predicted impact on reducing methane emissions for the U.S. oil and gas industry. While it is unfortunate that this is the reality, after writing about the regulatory process in the U.S. for the past ten years, it isn’t surprising.

In 2020 I wrote an article titled, “Exxon Now Wants to Write the Rules for Regulating Methane Emissions,” commenting on the state of methane regulations at that time. In that article I quoted Megan Milliken Biven, a former federal analyst for the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, the federal agency that regulates the oil industry’s offshore activity.

“Regulatory capture isn’t really the problem,” Milliken Biven said. “The system was designed to work for industry so regulatory capture isn’t even required.”

So let’s review how the methane regulations have been designed to work for industry.

Defining the Problem

The Permian region in Texas and New Mexico, where Exxon just closed a $60 billion deal which more than doubles their Permian holdings, is the reason the U.S. maintains the top spot for global methane emissions. A study released this year noted that in some parts of the Permian, the methane emissions rates are as high as 9%. The New York Times article reporting on that study explained the root of the problem when discussing methane emissions in the Permian, “Operators there tend to drill for oil, not gas, and will simply release much of the gas that comes up into the atmosphere.”

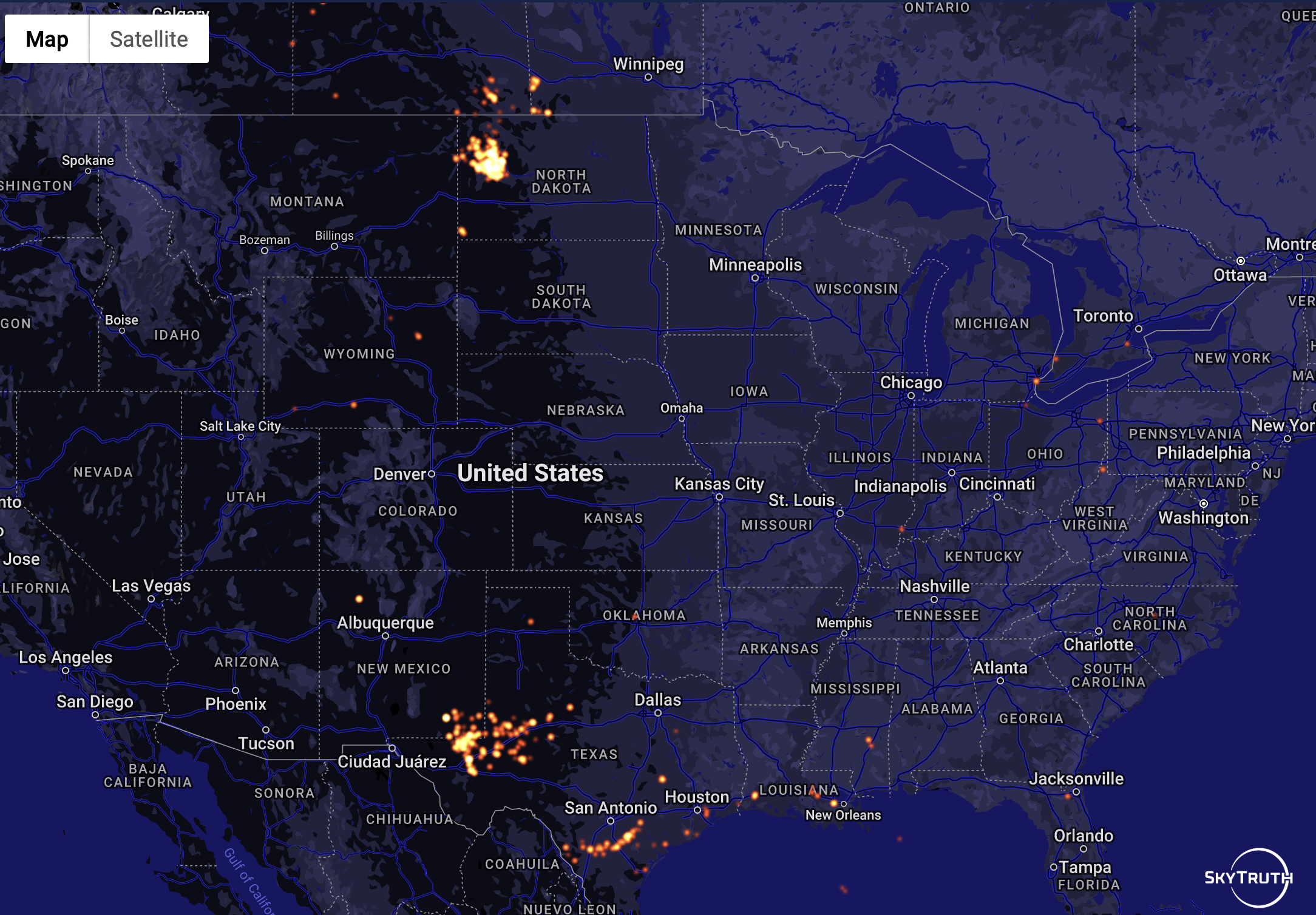

Image: Flaring of methane seen from space with the Permian and North Dakota's Bakken dominating the night sky. Credit: Skytruth

Multiple studies of the Permian regions of Texas and New Mexico have confirmed these high rates of methane emissions and a 2023 study identified the two factors that drove higher emissions in the region: new well production and low natural gas prices. That study was published in July 2023 in the journal of Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics with the title of “Continuous weekly monitoring of methane emissions from the Permian Basin by inversion of TROPOMI satellite observations.” The main conclusion on the drivers of growth in methane emissions:

“Periods of rapid growth in emissions were explained by enhanced development of new wells and sharp reductions in local natural gas spot prices.”

So now that we know what is driving the problem, how do the new regulations target these two known problem areas?

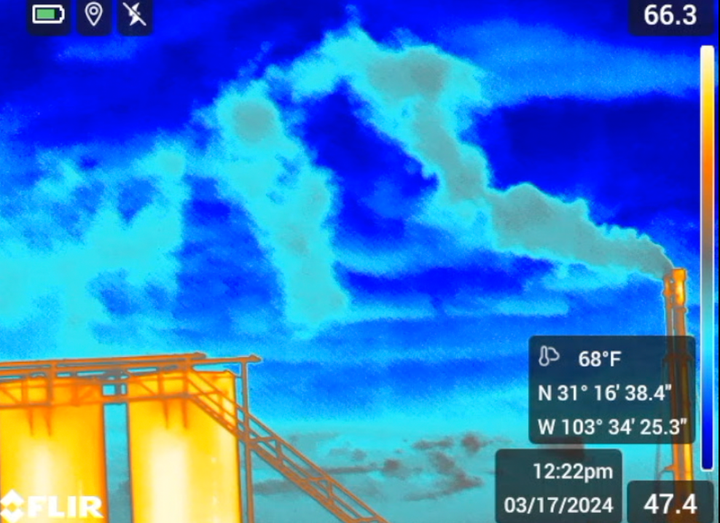

Video: Emissions at gas plant while gas prices were negative. Source: Oilfield Witness

Low Prices for Permian Methane Gas Drive Methane Emissions

In my 2020 article I wrote, “The methane currently produced in Texas’ Permian Basin spent a good portion of last year at negative prices. There is no financial incentive for producers in the Permian to voluntarily cut methane emissions in the current market environment.” The 2023 study mentioned above confirms this reality. And unfortunately, the methane regulations ignore this reality even as groups like the International Energy Agency routinely talk about how the rules will be effective because natural gas (methane) has economic value and that at least 40% of emissions could be reduced by oil and gas companies investing in the new equipment to reduce emissions — and then using the income from the additional captured gas to pay for that investment. However, when prices are negative it costs companies more to capture the methane gas instead of flaring it or venting it, so they take the low cost option and flare and vent it.

Last week, the BOE Report noted that, "Operators drilling for oil in Texas are scrambling to dispose of their excess natural gas amid a supply glut and weak prices, prompting an uptick in flaring requests."

They are doing exactly what they have always done and what the free market is telling them to do: flare and vent methane gas instead of paying someone to take it.

New Well Production

The correlation between new well production and an increase in methane emissions in the Permian is not surprising. Fracked shale oil wells produce at much higher rates in the first two years and then drop off significantly due to the high decline rates of shale oil wells. More production means more emissions. Here is a graph from the EIA of production from a shale oil well show most of the production in the first two years.

Source: EIA

But new wells also are granted exemptions while drilling and during the first ten days of production. In Texas, “Rule 32 allows an operator to flare gas while drilling a well and for up to 10 days after a well’s completion.” However, then there can be exceptions made if there isn’t appropriate infrastructure to capture the methane or transport it by pipeline. Which is currently the case in much of the Permian. Rule 32 states:

“In new areas of exploration, pipeline connections are not typically constructed until after a well is completed and a determination is made about the well's productive capability. Other reasons for flaring include: gas plant shutdowns; repairing a compressor or gas line or well; or other maintenance. In existing production areas, flaring also may be necessary because existing pipelines may have reached capacity.”

New wells will be allowed to flare if there are no pipelines and, as the Texas regulations note, these pipelines typically aren’t constructed until after a well is completed. It isn’t hard to see why new wells are driving methane emissions.

The new methane regulations allow operators up to two years of flaring exemptions if they can show that there aren’t pipelines to take away the gas, which as we just learned, is usually the case when they have completed a new well.

This is a second major flaw in the methane regulations. Unless you remember that they are designed to support industry.

The Methane Offsetting Loophole

The proposed regulations are not designed to address the two things we know drive methane emissions: low prices and new wells. The argument we are given for why these new regulations will work is that there will be economic incentive for producers to capture their gas. But the Permian prices eliminate those incentives. However, there will soon be a fee for producers for every ton of methane they release – over a predetermined threshold — and we are told this is what will change behavior.

However, the application of that fee has a major loophole that is essentially a methane pollution offset program. We know there are significant issues with carbon offset programs. Ever hear the story of the time someone sold the Vatican a forest that doesn’t exist? You know something is bad when an airline CEO calls it a fraud. A new article shows Shell dealing in “phantom credits.” Have you heard about “plastic offsets?” Kate Aronoff covered that scam this week in the New Republic.

Meanwhile, methane is 80 times worse for the climate than carbon dioxide. Meaning methane offsets — allowing producers to release methane if they can show that they didn’t release methane elsewhere — are much worse. The EPA has provided examples of how this might work. Let’s take a look at an example of an oil producing onshore well and a processing facility.

Source: Examples of charge calculations under the proposed Waste Emissions Charge, EPA

Here we see an onshore oil well production that produces 6,000,000 barrels of oil. The allowed methane emissions for this activity are 10 metric tons (mt) per million barrels of oil or 60 metric tons. Anything over that results in a per ton fee of $900. Based on the calculations done by the owner of the wells, the oil production actually produced 400 metric tons of methane resulting in a violation of 340 mt which would be a fee of $306,000. But that is without applying the methane offset (known as “netting” in the regulations) allowed by the new rules. In this example it is just a facility with two separate potential sources but that is all it takes. The calculations for the processing of the oil resulted in an estimate that was 3,540 mt below the calculated threshold. So now there is a 3,540 mt methane offset available to be applied to the oil well emissions and the result is no fine for the emissions.

I asked the Environmental Protection Agency if the oil well had actually emitted 3,500 mt of methane if the offset would cover all of that and they confirmed it would. Remember this is an example from the EPA on how they expect the program to succeed in reducing methane emissions and in that very example it does not do that and also doesn’t penalize the operator for its methane emissions. More business as usual. Of course, if it was the first year or two of the oil well’s production, it could be exempt from all of this anyway. Then add in the fact that the gas doesn't have any real economic value. Does this system incentivize producers in the Permian to capture more methane when it has negative value? No.

What if the rule didn’t allow the offsets and the operator was penalized? A fine of $306,000 seems like it is enough to change behavior except for the fact that would be a fine for producing six million barrels of oil, which at a market rate of $80 a barrel, is worth almost a half billion dollars. $306,000 is a rounding error in this situation.

Additionally, when considering this example, we must assume that these calculated thresholds and then self-reported emissions for the oil company are all accurate and everyone is being fully up front and honest about the methane releases. Based on the history of the oil industry’s methane reporting, these are bad assumptions. This raises another issue I will explore in a future article: enforcement. Even if these regulations were written to actually reduce methane emissions, the main challenge is enforcing them in an industry that has a long history of lying about emissions and fighting any regulations. And from a logistical standpoint, these regulations are impossible to enforce.

The Moment of Truth

Last week Amy Westervelt wrote about the choices we face with the liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry and the risks of producing natural gas/methane.

“With gas, the moment of truth is now. We’re in it. It’s not a story of what a company knew 50 years ago and buried. We’re not reading about a decisive choice between two paths that was taken decades ago. This is the story of what Big Oil knows today, and what governments are going to let them get away with.” Amy Westervelt, Drilled

The proposed methane regulations are designed to let them get away with it. We know the oil and gas companies know the risks of LNG and natural gas. We know they don’t care.

These methane regulations will not produce the promised results. The lawsuits by Texas and North Dakota to challenge the regulations are also in progress, once again letting us know that the oil industry will fight any regulation designed to protect the public, environment or climate if it cuts into their profits.

We need to solve the methane emissions crisis in the oil and gas industry. The industry will not do this willingly and we should not fool ourselves into hoping the current plan will change things or deliver the results we need. We are going to need a different plan if we want results.

Endnote: Yesterday the EPA wrote a letter to the American Petroleum Institute (API) letting them know that the EPA is using its “discretion” to respond to a request by the API to change the regulations. One of the two areas the EPA will be reviewing is “temporary flaring provisions for associated gas in certain situations.”

Comments ()